I climbed 黄山, Huang Shan or Yellow Mountain this weekend. It is not very yellow in fact originally it was called 黟山 Yi Shan which meant Black Mountain which is also odd as they don’t look very black to me either. It was renamed after the Yellow Emperor, a mythic patriarch schoolchildren learn about. The only thing that is actually logical is the Chinese character for mountain, which looks exactly like one 山. Three vertical strokes with a taller peak int he middle. 山 Is one of the earliest pictographs in the language drawn by Barbara whose other great contribution to Chinese civilisation was (.)(.) The fact it is not called Babs Mountain is an affront quite frankly.

Black or yellow? Let me share some pictures so you can make up your own mind.

Yellow Mountain sits pretty at around 1,800 metres tall, in Anhui province in eastern China. I started at 800 metres and it took me two hours to climb roughly 800 metres of vertical gain to my hotel, at around 1,600 metres. For comparison, Snowdon from Pen y Pass has roughly 800 metre elevation gain and usually takes double the time. Why so fast? How so quick?

Steps.

I thought I climbed Huangshan the easy way, one big flight of stairs and two hours later I was at the top. I at least expected a meritocracy at the summit, but instead I arrived to crowds of people who had floated up by cable car, apparently the engineered steps with uniform tread wasn’t easy enough. At the peak I saw jackets still creased from the shop floor, all collecting the same reward without the effort. The mountain is UNESCO protected but too accessible, so the view no longer felt earned. May as well take a look, enjoy my efforts.

Its sheer granite peaks and conspicuous conifers are only the foreground. The endless sea of mountains in the background stretching to the horizon are washed in blue, and the cloud inversions appear like carpets below you once you ascend.

You feel almost heavenly because you cannot see the ground anymore, and above your head the clouds hang so low you can watch rain forming. The landscape defined the entire aesthetic of Chinese painting, 山 水 (mountain & water) which is perhaps why it felt oddly familiar.

I had started the hike with a married couple, Ying Ying and Freddie. Born in Indonesia but truely a global couple who have lived everywhere and who move countries like I move house plants.

Huangshan requires a timed entrance booking, yes, nature has opening hours in China, so they guided me through the process the night before. Freddie, with his natural confidence around logistics, handled the queue, the map, and the entrance checks as if he worked for the mountain. Ying Ying has these small tattoos between her fingers, the kind that look like remnants of rebellion. She is alert, quick to notice warnings and signs, the person who makes sure everyone has water and nothing is forgotten. The upside to having an accessible mountain is a fancy hotel waiting for us at the top. Watching them together on this climb reminded me how a long marriage shapes people in subtle ways.

The first ten minutes were the usual mix of panting and small talk, all of us pretending to be less out of breath than we were. Freddie leads without ever announcing it, and Ying Ying fits herself into the spaces his certainty creates. None of this feels oppressive, only patterned.

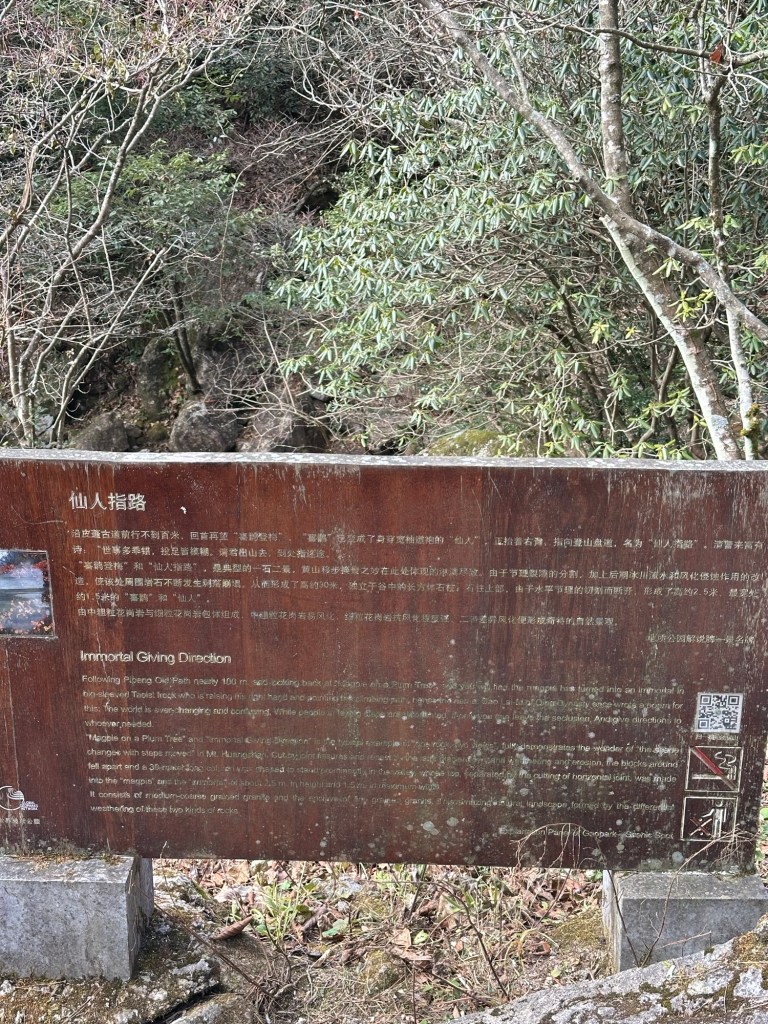

We enjoy some of the poetic way points along the way

As the steps continue without a single break, Freddie told me about the ten years he spent commuting from London to Scotland for work. He said it casually between breaths, describing airports, hotel routines, and enough loyalty points for Marriott immortality. Ying Ying added that she stayed in London raising their daughter, which she stated as a simple fact rather than a complaint, though there was a faint edge to it, a small tinge of resentment that slipped through the mountain air. I was not about to launch into a feminist evaluation. I did not have the lungs for it, still, the comment did ping patriarchal thoughts.

We reached White Goose Ridge and paused to drink water. It was crowded, but no one seemed bothered by the numbers. I offered to take their photo. They stood together, a comfortable couple with years of shared routine behind them. I told them to move closer. They did, but when I nudged them for a kiss, Ying Ying pulled back immediately. Freddie laughed and said ten years ago maybe. I was sad but what right did I have to morn their sex life. The comment said more about marriage than a full conversation ever would.

From there, the climb steepened. The steps continued and the clouds began to settle below us so the world felt suspended. I went on ahead and after roughly two hours I reached the North Sea Hotel at about 1,600 metres. It sits amongst a tight ring of peaks so it feels like you are staying in the middle of a stone amphitheatre. Freddie and Ying Ying arrived half an hour later, slightly flushed from the climb but still cheerful.

We checked in and the three of us had lunch. Freddie had an afternoon of planed walks around the top of the mountain. It was here that the shape of marriage finally made sense. Marriage is a fail safe for Ying Ying because the deal is uneven even when the couple is kind.

She is not unhappy and he is not the villain. He is one of the good ones. Their deal produced a life, a daughter, a shared retirement. He worked, she worked, and both roles mattered, but only one of them earned a pension and recognition. Patriarchy shaped him too. I think he’d love her to take the steering wheel instead of offering commentary from the passenger seat.

A wife’s dependency is not emotional, it is architectural. In many instances a husband’s job creates the income that opens up the world. Marriage keeps her safe if he ever wandered off with Babs. Without that contract she would be starting again at the bottom while Freddie and Babs ride the last cable car down.

Can a set of stairs up a mountain be an allegory for patriarchy? Women could carve a new route with a machete, take the long way, refuse the steps, but why would we when the route is already swept and signposted? So we take the stairs and carry everything else on the way up too: work, home, children, the invisible labour. Meanwhile the mountain peaks are still named after men.

His planned afternoon meant I could zone out while someone else navigated, so thank you patriarchy for the perfect sunset photo. And thank goodness for x2 zoom.

The apathetic me thinks the reward is not worth the fight, after all we can see in the gender pay gap that parity still does not arrive. If only the patriarchy could name some fucking mountains after us, or here’s a thought, let our children take our name, if that feels less radical.

The anarchist me says hijack the cable car, legalise sex work, and start charging for childbirth.

Post Script.

我上个周末爬了黄山。我在英国爬过很多山,所以我喜欢对比。 黄山虽然爬了八百米,但是只用了两个小时。在英国我爬的高度一样,但是时间要长了一倍。是因为黄山更陡,到处都是楼梯,速度更快,不过小腿更酸。大男子主义想黄山的楼梯。女士们直接爬楼梯或者创造自己的一条路。 一边爬山一边观察婚姻。男生的价值反映在他的银行江户里 女生的价值 却看不见摸不着。

That scenery is incredible!

LikeLiked by 2 people